Split-screen: Jesse Mockrin’s Narrative Paintings

Jesse Mockrin is a painter who developed a new compositional style and bounded forward in ten-league boots. It’s a weird balance between Mockrin’s single canvases and her dual ones. It’s like a muse stepped into her studio, or another part of her. The single canvases are sweet, stylized, with a hint of expression on the staring faces of people always from the same parents. They feel like childrens’ illustrations. She often doesn’t fill the whole canvas but places what matters in the lower half.

And then POW! come the big divided canvases with assertive gestures, galloping horses, abductors prowling through the reeds. And the conscious use of competing narratives, mixed messages, spin, paradox. When she shifts to the dual canvas we move from simple tales to raging myths. Agitation enters the action, id. And that edge that forces you to admit you don’t really get it. What is, isn’t. The devilish joinery has first sold you on a shape no firmer than a teapot made of clouds.

I’m cloudy on Mockrin’s exact chronology so the comparison I’m making is between paintings like the opening image above and paintings like this below. Compare the differing challenges to the artist, her use of canvas space, the stasis and energy, the can-opener used or withheld on her emotions.

____________

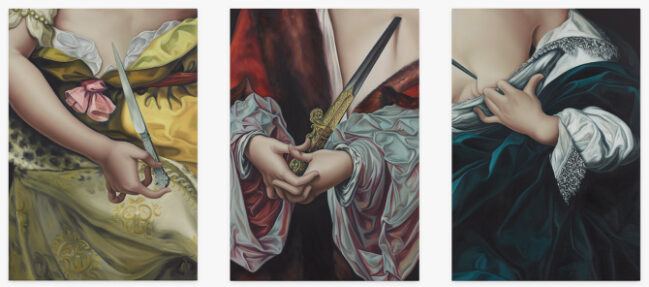

“Repetition cannot make it less” is three versions on one canvas of women about to plunge daggers into their chests. They each are shown from below the shoulders to perhaps the lap. Faceless. By their dress they lived some hundreds of years ago. Suicides were expected of women compromised inside a morality framed by men’s ownership of them. Imagine being the victim of violent rape and your response is to kill the victim, you.

And it’s one thing to pick up a stiletto, quite another to convince the hand to plunge it into that hand’s own flesh.

In all three canvases action turns inward, each woman about to end her life. The hands are focused each on her own weapon and the action belongs to the heart of each canvas.

____________

You approach a canvas of course as one entity. Our brains make little of Mockrin’s mid-canvas stripe — a trope we may think — until you’re enough engaged with the forms to realize something is very wrong. Perhaps you attempt reading it as two panels. Maybe Chapter One and Chapter Two. Good luck.

Here we encounter something biologically based and inexplicable. Human DNA codes to recognize stories from other forms of language. Treaties, philosophies, poems. Why this should be I have no idea but I’ve watched it happening for years. Before, after, maybe furthermore are tied to our endorphins.

In cats’ retinas sensitivity to quick movement is also built in. Think mice. I imagine us humans catching wind of a story as standing alerted like Disney’s Remy in Ratatouille, a rat with its pink pointy nose and whiskers quivering. “Oh, a STOR-RY.”

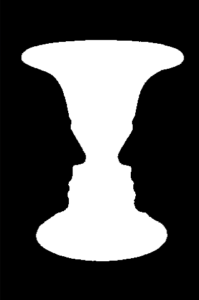

And this is what Jesse Mockrin has harnessed in her dual paintings. Each painting, left and right, must ultimately be read separately. It’s like trying to read a Rubin’s Vase. The famed visual illusion is a paradox, you can either see two facing profiles or the vase shape they make between them. You can’t see both at once.

The white stripe down the center of a Mockrin canvas is where meaning pivots. They are one::they are two. They are Rubin’s Vase.

Step back and then Mockrin’s composition explicitly owns the whole canvas. Left and right merge into impossible bioforms, cohesive shapes that balance the overall space. In visual art, alignments getting two lines to meet, or similarly colored forms to merge has suggestive power. It can lull you into false assumptions that only better looking can untangle. Mockrin’s deliberate and exacting alignments may have you believing a head is growing where a second arm should be.

Here hands are in manacles on the right and in sexual seeking on the left. We toggle for a truth here but can’t find one. Not finding one is Mockrin’s point.

That arm at far left. Is this a single chase or one that repeats and repeats forever? The word Syrinx means a Panpipe. In Greek mythology Syrinx is a chaste nymph who is chased by the god Pan to the edge of a river where she pleads with the river nymphs to save her. They turn her into hollow reeds that play sound when a breeze blows over them.

Chased. I’m a woman and I’ve read mythology since childhood. I never read “Tried to violently rape an unwilling and terrified woman.” I read chased and read greedily on. How cleverly we are shackled.

____________

I cannot say why the motifs of barbarous female suicide, raw abduction, hurt and cruelty are so strong in Mockrin’s work. Nor do I feel I need to ask. The lurid worst of tabloid journalism. How Mockrin handles paint is what I try to understand. What she shares or withholds from the many moments of her life cannot affect the quality of her art. Emotion runs deep in her, yes, but to probe where you don’t need to says more about you.

And if Mockrin wants instead to issue a boiling manifesto with every painting, that’s also up to her.

I note that none of her many pointed daggers has drawn blood.

____________

Mockrin is onto something different. I’m not claiming that out of the whole panoply of image making history she’s unique, but I am saying that I think a lot about how you can join images and I’ve learned something new from her.

___________________

see also:

Was the Chauvet-Pont d’Arc Cave the First Movie Theater?, by Marc Azema

Chauvet Cave, Official video of France

Another way to show motion