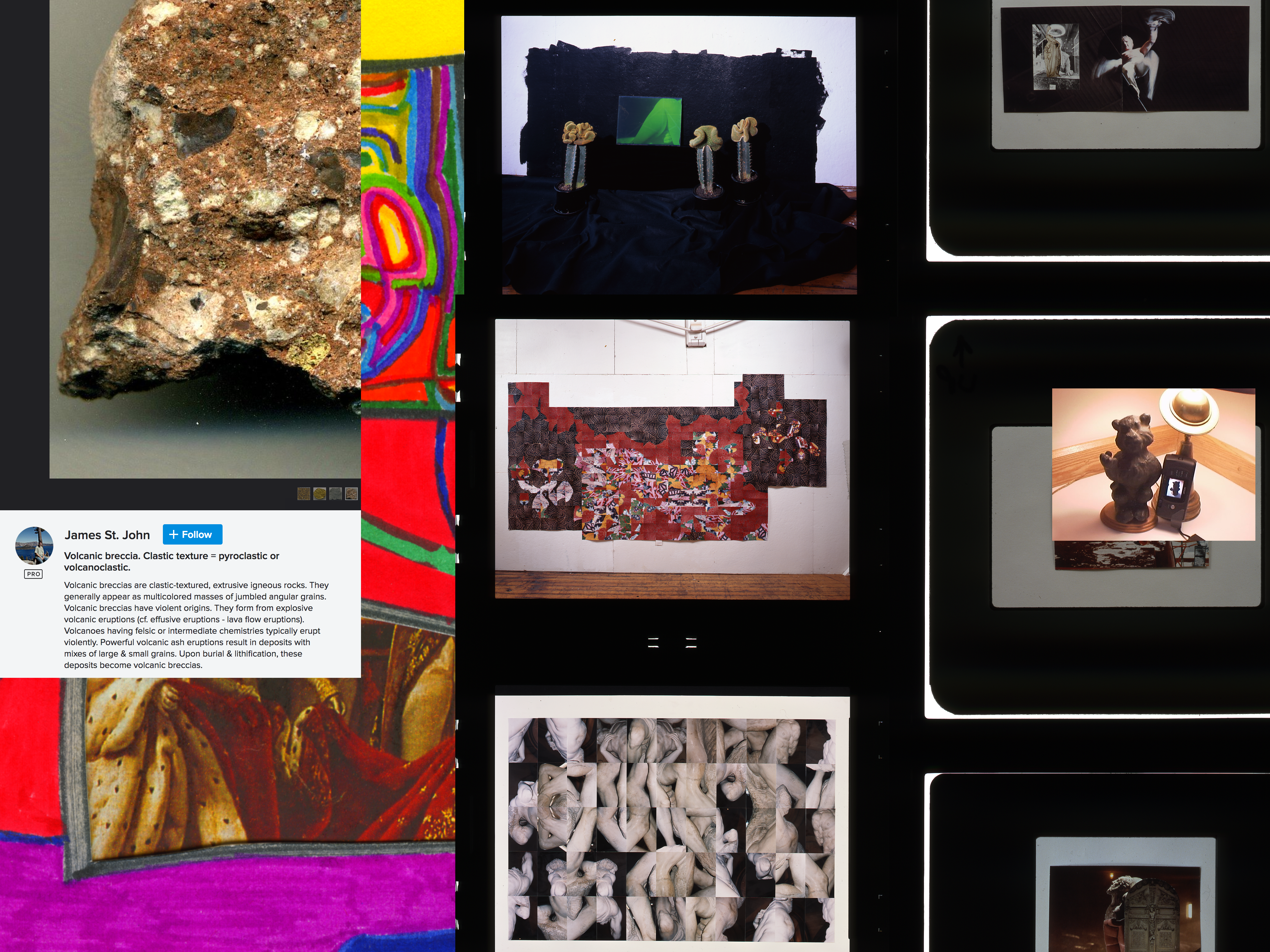

Clastic Art

For years I’ve referred to my style of artwork as Clastics. Some people strongly object because of its association with plastics. Elastic I say to them. Fantastic. Orgiastic.

I’ve never seen an object, never seen an image, that couldn’t belong in a work of art. The best definition I’ve found for it comes from geology: clastics.

Clastic rocks are composed of fragments, or clasts, of pre-existing minerals and rock. A clast is a fragment of geological detritus, chunks and smaller grains of rock broken off other rocks by physical weathering.

Substitute culture for rocks and you understand. Cultural detritus, chunks and smaller… In my art a 19th C cartoon has equal value to a photograph of a chemical plant producing a chemical that wasn’t developed until a century later. But if the cartoon has a soldier in a red uniform that chimes well with the red of the roof of the chemical works, then maybe they speak.

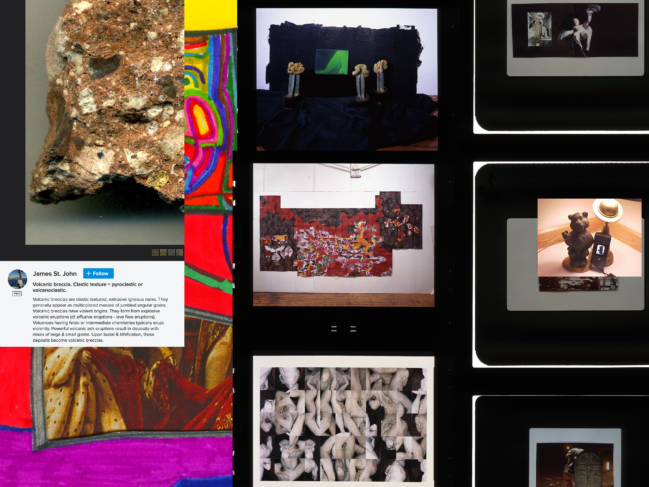

The content of each image both contributes to the meaning and doesn’t matter at all. In the composition you discern from a distance that all that matters is the balance of colors and forms. A well-formed abstraction. Up close, at reading distance, what the images are of and also their style inform your understanding. This happens inside of me and I can’t tell you the recipe. Could Gauguin articulate why he put that red-gold color in the right corner? This is the great mystery of visual art: something unspeakable ignites the life.

In the real world outside the picture plane the same rules apply. One of my installations, Ezekiel, used two stacks of strobe lights that faced a wall that was coated with aluminum sheets on one side to reflect the glare, and with tarpaper on the other to blot it out. The excitement was supposed to be on+off on a random timer, but my electrician convinced me that none could logically exist. This was an Open Studio event, I was always there with a controller in my pocket. On an Open Studio budget, purity be damned.

Which reminds me of one of my all-time favorite artworks, the first winner of Decordova Museum’s Rappaport Prize for barrier-breaking art. Jennifer Hall’s Acupuncture for Temporal Fruit still affects me in memory for its insidious roping of the viewer into a situation of moral ambiguity.

You walk into a gallery, white canvas in your mind, unknown, about to be known. Techie-looking sturdy plastic containers, little tents, hang in a line from the ceiling. In each, a tomato. Also a mechanical arm wielding an acupuncture needle. But only when someone is moving in the room. You wander, the sensors click, another stab into a tomato. The tomatoes are in various stages of flowing juice and decay.

If no one entered the gallery those tomatoes would still be rosy whole. But then you read the placard on the wall, the Writing on the Wall, and you’re as complicit as a witless Joseph Goebbels believer. It’s you doing something evil-feeling manipulated by a will cleverer than yours. By fate unseen and inescapable.

The damaged tomatoes confront you. It smacks of Animal Farm, of 1984. You’ve been deviously manipulated into a guilt you had no part in earning. So assess your guilt — and swirl it down the drain-hole of the repeating mirrors of a Lucas Samaras walk-in box.

Except it won’t quite go away.