Mami Kato’s Quiet Power

It’s instructive that the the introduction* to the 2019 exhibit of Mami Kato and her husband Michael Hurwitz was written by the consummate artist Martin Puryear. Mami Kato deserves his respect.

Kato seems disinterested in the chatter of the world. It seems that making objects is more a meditative practice for her than is plain image-making. She devotes time to build from bitty bits to forms with that gather meaning. (I’m not sure if she thinks of them as sculptures.) She was born in Japan and her working style reminds me of master netsuke carvers, with their disciplined ability to carve a swath of pattern unyielding in scale or style. Kato’s power is quiet like theirs.

For artists like myself there is the lure of variance, the urge to follow change, to find out what’s hidden behind the next hill. It’s important to see how different Kato’s practice is. Deliberate and disciplined. She can color inside the lines once she draws the lines. I would guess that slapdash feels substandard. She’ll concentrate for whatever time it takes to get her effect. The accretion of handwork into a formal statement.

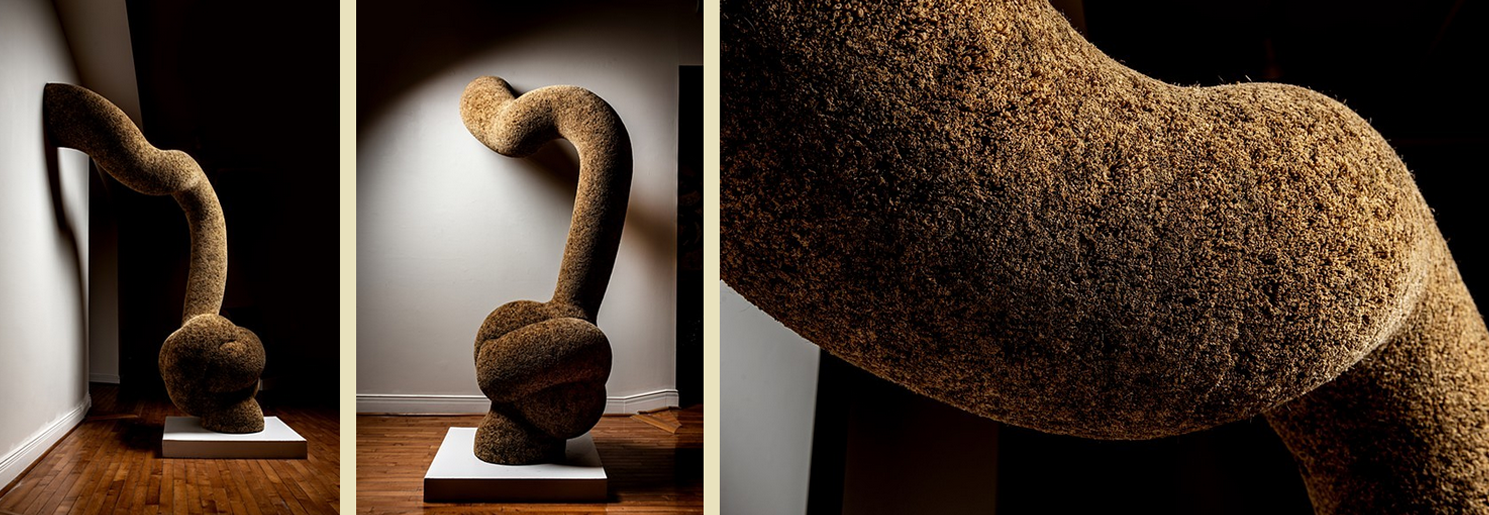

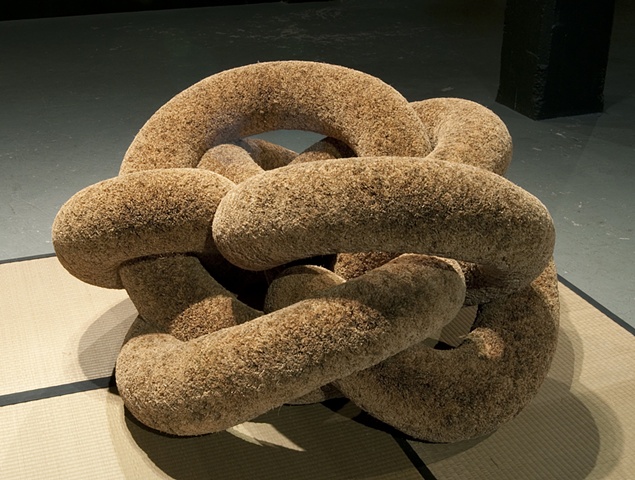

I’ll focus on Big Knot here because it’s the first of Kato’s artworks that stopped me in my tracks.

I want to ask her things. Did she see the Big Knot form all along? Or did it teach her where it wanted to go as she built? Did she understand the scale as she began Big Knot, foresee the fat slow curves, the gentle asymmetry? She uses the same technique in other works at different scales and rates of curvature.. I want to ask why the knot is not exactly a knot and why it’s low, and only low, in the form’s expression.

There is a portrait of Kato and her husband with Umbilical Field in the foreground. It’s much bigger, much more primal than you think.

I recently watched an interview with the author Margot Livesey about her new book The Boy in the Field. She said that at one point she realized that she was going to be able to pull off the novel she wanted, and stopped worrying.

Did something like this happen with Kato? You start building, having faith in an outcome but never assured — until the artwork tells you it intends to succeed.

Kato starts with coarse rice-stalk rope she buys from Japan. She unplaits the rope, cuts short lengths — which look precisely measured — and adds them bit by bit to a developing shape. There’s a wonderful story here with multiple decision-points, were she to tell it. From when she first holds the rope in her hands through the final furry-and-smooth resolved form.

The effect of these bristly tubular shapes is soft. Velvet pile. You sense you might rub your cheek against them. Don’t. The contradiction is part of the artwork.

____

Oddly I’d been struck by a Martin Puryear work that feels kindred to Big Knot. Oddly because I hadn’t read his introduction for the exhibition yet. I enjoy how the forms have a family resemblance without either one mistaken for the other.

____

____

Purity is another word that Kato’s work deserves. Purity of intention. Her website offers a look back at work that dates well before today. Kato has journeyed. Early her forms were full of question marks and pauses where a verb might go. She has grown herself up to clarity. Her more recent work shows the assurance of a mountaineer who can plot her own path in a forest.

Another view of Kato’s practice here. Eggshells, fragility spoken aloud. Look at the tight snarl of the knot. You could not achieve that without experimenting to test the limits. With real eggshells, already emptied, wiped of yolk, bought with patient labor. See all those sacrificial shells when you contemplate this.

Compare the complexified curves of Egg Formula with the quasi knot in Big Knot. The ambling curvature of bulk. The complex flight path of the airy eggshells.

________________________

* Introduction by Martin Puryear. Unfortunately I need my biggest monitor enlarged to the max before I can read this.

On complexity (and a fine contrast to Kato’s work) Michael Hansmeyer and the Fourth Industrial Revolution