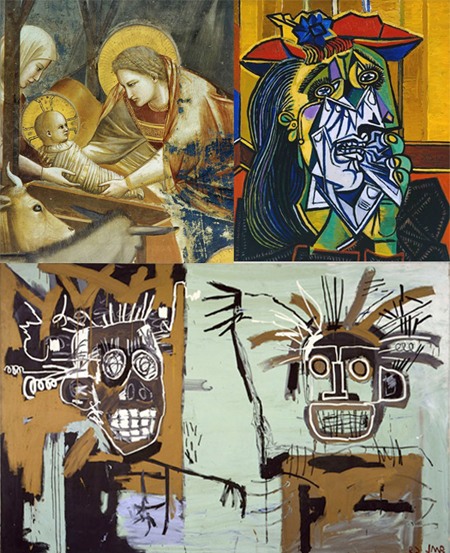

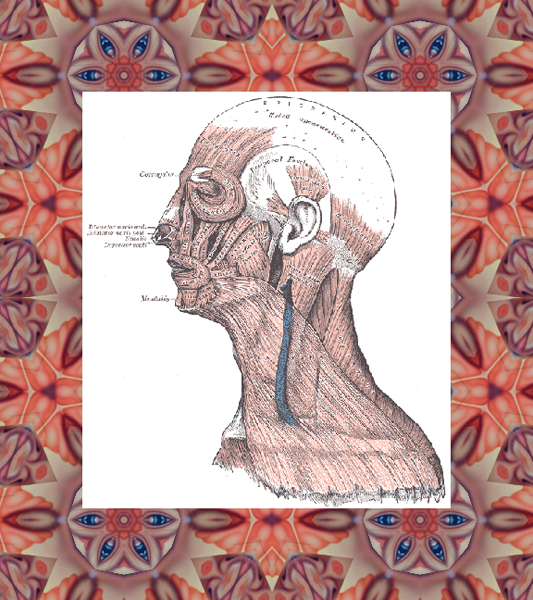

Muscles of the human head from Gray’s Anatomy. via WikiMedia. Pattern, Sloan Nota.

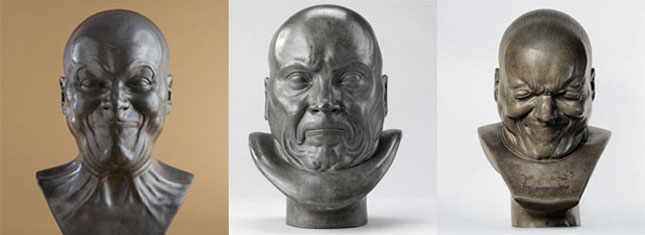

The muscles of the human head are numerous but finite. With them we make every facial expression known. And every artist who wants to portray human emotions is bound by what these muscles can do. Keep that in mind as you watch this animation of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s so-called character heads morph in sequence.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YXpgrfldYHI[/youtube]

Getty Museum animation that morphs from one of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt’s character heads to another. The artists are Edward Rose and Nick Reynolds. via YouTube

Today we look at how the 18th century sculptor Messerschmidt and the modern painter Francis Bacon abstracted form from the facial givens. By abstract I mean take a whole lot of visual information and isolate only the elements that clarify your point. Think of chemists driving off impurities to create an unadulterated substance.

Messerschmidt’s heads are not anatomically correct — surprising given their realistic feel. Draw a line from pate to chin down the middle of the nose. The right and left sides are identical. We know that nature creates a certain lopsidedness — one eye larger, an ear lower — but Messerschmidt wasn’t aiming at portraiture. He’s analyzed the baseline components of human expressions and given us a double helping in each head. Emphatic creases, bald emotions, a gamut of human psychology.

Look at these similar pursed-lip men — tagged (after Messerschmidt’s death) as The Difficult Secret, The Ill-humored Man and The Incapable Bassoonist. See how the mouths and chins are held constant. But compare the brows, the upper lips, the Secret’s nostril flare. The Ill-humored man’s head is cocked haughtily but his eyes alone refuse to see.

The following examples show what Messerschmidt could convey by the set of the shoulders, the taut tendons of a neck. These gentlemen are The Strong Man, Afflicted with Constipation and An Arch Rascal. Again closed mouths but so very different from the ones above.

You can appreciate Messerschmidt’s genius for distilling unique human emotions from the welter of things our faces do. For we are subtle. To depict a Machiavelli, blend a few of Messerschmidt’s expressions with a soupcon of another, make one eye narrower and and lean his head slightly to the left. Messerschmidt’s heads show brazen monomaniac emotions that we’re normally too guarded to display. And too rich and complex to feel for very long.

Messerschmidt, gone since 1783, remains a draw for the modern imagination. Artists find inspiration here, galleries and museums build shows around the work. There have been at least two exhibits since 1998 pairing Messerschmidt and Francis Bacon.* We’ve looked at Messerschmidt’s artistic strategy for abstracting from the immutable facts of the face. Bacon had no choice but to do the same.

________________________________________________________

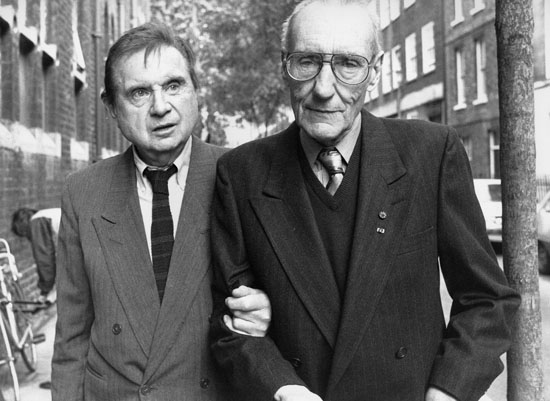

Francis Bacon and William Burroughs via soundcolourvibration

The British painter Francis Bacon (1909 – 1992) had a weird dish-plate face. A medical condition? If you know his work you know he must have suffered emotionally too. His humans often look out at you from a canvas — past the mask of their deformities, sad as chimps in a low-rent zoo. Not the screaming Catholic clerics but the self-portraits, portraits of people he knew.

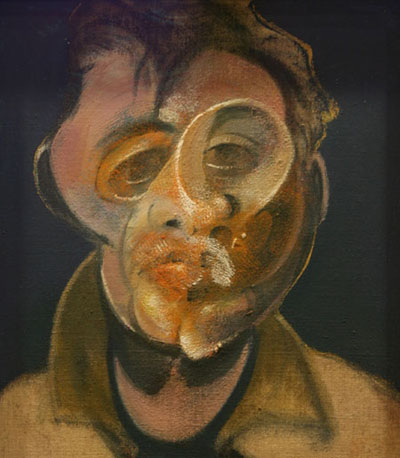

Francis Bacon self-portrait via slowmuse

To compare a sculptor and a painter can get phantasmagoric. I start from a premise you may not share — but try the thought experiment. Pictorial space is the depth represented in a painting, a depth-ful image on a 2D plane. For me this pictorial space can be deeper into a picture than you could walk in a day — a wide road at your feet disappears into distant mountains. Or the Bacon head above could command a space no shallower than a Messerschmidt. His figures twist and cringe in physical space. The face above is segmented as the shell of a horseshoe crab, its parts may be in different spaces — or in unsequential times.

Now crank your mind around to a seemingly unrelated thought. Imagine yourself as an artist of Bacon’s vision whose medium is digital 3D — CG, character generation. How would a Bacon exploit his medium expressively? Is Bacon carving space with a melon-baller? Did he experience shaping as like modeling clay or as chiseling marble? I admit it’s idle to wonder about Bacon’s seeing and seizing of forms but I do.

Or did he hold a distorting lens over flat segments of a face ? Distortion on a 2D plane, a magnifier over a nose, and did he not feel he was sculpting in 3D at all?

When I think in these terms about spatiality I’m not asking how Rembrandt conceived it. Because for his generation space just was. Ergo invisible. Nor am I thinking about the space that Cecily Brown paints. Carving’s not her interest. To me her space is often at a steep tilt as if an industrial window was dropped open on a short length of chain..

Self-portrait by Rembrandt via thewhitereview The Girl Who Had Everything (detail) by Cecily Brown via saatchigallery

____________________________________________________

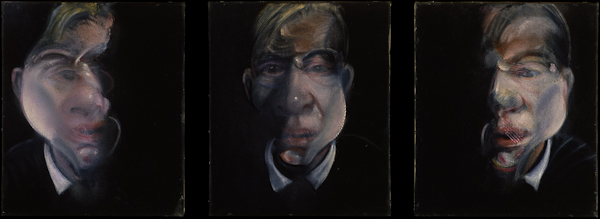

Below are studies Bacon did for self-portraits in the 1970s. Clearly he’s moving the mass of the face, tugging, scooping, but never so awry that you can’t read it. Ovals, circles, arcs, swoops. Angles aren’t going to say what he needs. And there’s the give-and-take of what’s distinct, what’s hazy. So unlike Messerschmidt, so unlike a natural face. So human.

Each triptych lets us study the internal painterly variations. As we did with the triplets of sculptures above we can ask what the artist is changing, what the constants are. In the 1974 studies each face has an off-kilter racetrack that circles the end of the nose and seems to divvy the face. Yet the jawlines of each are unique. And the ears, the unseeing eyes. However the middle head is modeled more deeply than its brethren — see the gouged area beside the nose and the accentuated canyon from the ear to one iteration of the mouth.

Three Studies for Self-Portrait, by Francis Bacon. 1974 via ananasamiami

Three Studies for Self-Portrait, by Francis Bacon. 1976 via ananasamiami

3 Studies for a Self-Portrait by Francis Bacon, 1979-1980 via berkshirereview

Messerschmidt’s project had a documentary aspect. Gray’s Anatomy likewise catalogues physical facts. Messerschmidt was also bedeviled with visions that his sculptures sought to appease. There’s historical confusion — was he actually mad? He fulfilled normal commissions in the same time period. And it’s not only space that we think about differently now.

Bacon’s project was to document, or reveal, something else. (Or was it?) Interior reality not literal flesh. Bacon’s abstractions had to follow rules not of the mirror but of that yes inside artists: Yes this image is true.

Francis Bacon self-portrait via andrewgrahamdixon

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

________________________________________________

Extra credit material:

On the blog mostperfectworld this lineup of Messerschmidt character heads is most wonderfully compared with some found pumpkin art in Brooklyn. I find this blog quite wonderful.

On a street in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, 37 small pumpkins, carved like jack-o-lanterns, remain long past their autumn-prime, impaled on the posts of a wrought-iron fence surrounding a handsome brownstone. (The parodied image of a gothic fortress comes to mind.) Presumably, these pumpkins have kept their vigil since mid-October; having survived Hurricane Sandy, perhaps their owners didn’t have the heart to later depose them. Through the winter, the heads have weathered: toothless grins now sag and gape; eyes squint and yawn; foreheads have caved-in; the pumpkin skins are discolored; some heads have nearly melted while others are turned to leather. Now February, the heads have accumulated small personal histories which they wear in their grotesque, and surprisingly comic, expressions. To have thought, immediately, of Messerschmidt’s “character heads” is probably a careless (but undeniable) impulse, a facile comparison that is satisfying in the extreme.

I urge you to enjoy the animation of these Brooklyn pumpkins at mostperfectworld and to thoughtfully compare it with the Messerschmidt video at the top of this page. The pumpkins also share strong kinship with Bacon’s soulful deformations.

__________________________________________

* The Bacon and Messerschmidt exhibits were:

- • 2006. Francis Bacon and Franz Xaver Messerschmidt — Compton Verney, Warwickshire, England.

- • 1998. Francis Bacon, Louise Bourgeois & Franz Xaver Messerschmidt — Cheim & Read, New York, NY. This exhibit was the first time I’d seen any Messerschmidts. A stand-out exhibit I can still recall after hundreds of forgotten ones.

- via artfacts

- Nick Reynolds makes death masks

- Alabama 3, the band he’s in

- The Heads of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, a review by Christoph Friedrich Nicholai in The Paris Review.

- Messerschmidt and Modernity, a Getty Museum Show, 2012

- Franz Xaver Messerschmidt – review, by Jonathan Jones in The Guardian

Francis Bacon

- Francis Bacon News Archive

- Movement Nu 21: Francis Bacon Documentary by South Bank Show, at soundcolourvibration

- Francis Bacon: behind the myth, by Rebecca Daniels at The Telegraph